Seo Taiji 1992-2004: South Korean popular music and masculinity (my master's thesis)

© Janet Hilts 2006 - please note: this is not the final version of my thesis.

Fraternity

The most noticeable theme of masculinity in “Hayôga” performances is fraternity or male bonding. In Japanese popular music from the same era, male stars that display androgynous or feminized images (Kimura Takuya for example) often use male bonding in their performances or television appearances to reassert more traditional manliness (Darling-Wolf, 2003). Similarly in Taiji’s “Hayôga” performances, male bonding as well as the inclusion of the group Samulnori into the performances, help to reassert more traditional manliness while excluding females from participating in the performances. However, the oppositional character brought to these performances through new and noisy aspects of the song and visual performance (dance and creative camera work) temper hegemonic masculine displays by confronting norms of adult society, a society whose social order is reliant on powerful forms of masculinity as men’s—militarized for instance— and on and gender imparity. The “Hayôga” performances then are ambiguously placed between subordinate and powerful masculinities.

WHERE ARE THE GIRLS?

Fraternity or male bonding is central to the overall feel and look of all three “Hayôga” performances. A number of actions or scenes illustrate this. For example, figure 10 shows Taiji and Boys mingling together with the members of Samulnori as they dance, as if all are friends partying together. In figure 11, Taiji and the Boys are rapping and hanging-out with other young guys in a small bar, enjoying themselves while sitting on the stairs and then by the bar.

Indeed the whole music video comprises of scenes of young guys hanging out or hip hop dancing together. Much of the 94 Yôrûm saeroun tojôn performance consists of Taiji and Boys joyfully trading rap lines and the relaxed choreography brings a feeling to the performance that they are essentially just friends hanging out together on stage.

The fraternity of these performances is in essence hegemonic, providing power to males by excluding females from active participation on

the stages or in the video. A central aspect of hegemonic masculinity in contemporary South Korean society is males’ command of public society at the expense of female participation. Even though they are simply performances of a popular song, “Hayôga” performances demand investigation because they include such a fraternity and lack of female participation.

In her article “Image is everything: The marketing of femininity in South Korean popular music” (2005), Heather Willoughby writes:

Sexism, or the dismissal and marginalization of women, is as apparent in the pop music scene of Korea as it is elsewhere. Male performers dominate the scene. The exceptions to this are groups such as Roo-ra who included women, but in a subordinate role, or male bands surrounded by a large group of female dancers. In shows I observed in 1996, several groups consisted of three or four male singers with an additional two to six dancers who were almost exclusively male. If female dancers were included, they were usually set on a separate stage behind the singers, and the camera only occasionally panned to them. Female singers, too, when included as part of the group, generally remained in the background dancing for the majority of the song and, coming to the foreground only for a brief solo (Willoughby, 2005: 7).

Seo Taiji and Boys’ performances of “Hayôga” fall within the trend that Willoughby outlines, despite the group being famous as socially progressive. The performers in these performances are as follows: The 1993 live performance of “Hayôga” (93 Naeil ûn nûjûri) includes highly visible traditional musicians (Samulnori) and the backing band in addition to Taiji and the Boys. The additional performers in the 1994 live performance (94 Yôrûm saeroun tojôn) are the backing band. In these two cases, there are no female performers―no band musicians, additional musicians or dancers. The video of “Hayôga” also includes no females, despite there being approximately 20 additional extras or characters contributing to the video’s narrative, mood and look.

Some may not be concerned over the lack of female participation on stage or screen in these performances because “Hayôga” is primarily an expression of the spirit of shinsedae and the issue of female versus male performers is irrelevant. Indeed Taiji and Boys and their songs and performances are almost exclusively examined in terms of youth culture and its changes, for example by Howard (2002), Lee K-h. (2002), Morelli (2001), Shin (1998) and Kim (1999). The youth culture angle of these writers is certainly important to understand Seo Taiji and Boys, but there remains the problem and significance of females being shut out of Taiji and Boys performances. Considering Willoughby’s comments, “Hayôga” falls within a majority of early and mid 1990s groups who excluded or marginalized female participation in live performances and in videos. Given this context, one may suggest that “Hayôga” simply falls into this trend, sharing a mood of male bonding and a male-only cast of dancers and performers with other videos such as Deux’s (Tyusû) “Yôrûmanesô” (1994) or Lee Hyun U’s (Yi Hyôn-u) “KKum” (1991) and should not be criticized. However, I find it difficult to align these videos simply with youth culture (shinsedae munhwa) and ignore the fraternity exhibited in their images when they so obviously lack any female participants. A music video that should be seen as a genuine example of inclusive youth culture performance and does not fall into the fraternity trap is Cool’s (K’ul) “Nôigil wônhaettôn iyu” video (1994). In this video the female group member has a role and image exactly the same as the guys and is filmed, staged and framed the same way as the male members in the group; the female member’s movements, attitude toward the camera and clothing and hairstyle, perform the same gender as the boys’. Although it could be said that Cool were basically imitators of Seo Taiji and Boys, in this video they do a much better job at contributing to the construction of a unisexual or inclusive youth culture than do Seo Taiji and Boys in any of their videos or performances of the early to mid 1990s.

At around this same time, a similar marginalization of female participation occurred in Chinese popular music. In his book China's new voices: popular music, ethnicity, gender, and politics, 1978-1997 (2003), Nimrod Baranovitch deals with the problem of the marginalization of females in 1980s and 1990s mainland Chinese popular music when discussing the music of Cui Jian. Jian, a popular musician associated with a new youth culture who writes songs of social and political resistance, shares much with Seo Taiji. Baranovitch writes:

The relationship between political resistance and masculinity is articulated in Cui Jian’s “Opportunists” (Toujifenzi), the song that the rocker dedicated to the hunger strikers in Tiananmen Square during the 1989 struggle to bring about change, and to demonstrate courage (“Oh…we have an opportunity, let’s demonstrate our desire / oh… we have an opportunity, let’s demonstrate our power”). Though this call is not gender-specific in its address, other lines in the song nevertheless reveal a clear male-centric attitude and suggest that Cui Jian is addressing only male demonstrators, as if the whole movement was a celebration of masculinity or a test of masculinity. The implication is that it is only men who are expected to demonstrate their desire and power, and that desire and power are the criteria for masculinity, as if women did not share these qualities... “Opportunists” supports Lee Feigon’s suggestion that “the men in the student movement, though enlightened about many of the inequalities of Chinese society, were not particularly enlightened about the roles of women in society,” and that “in both the official and subversive acts of political theater performance in 1989, women were relegated for the most part to traditional kinds of supporting roles” (1994, 128) (Baranovitch, 2003:117).

It is difficult to ignore Jian’s exclusion of females in his lyric’s address and the overall exclusion or marginalization of female participation in 1989 Beijing performances and to generalize these male-centric songs and performances as constituting a new youth culture in China. It is similarly difficult to generalize Taiji and Boys’ performances in such a way. Despite being outwardly concerned with social issues like Jian, Taiji in his performances reinforces the normalness of males’ public participation while othering that of females. Furthermore, the dominating masculinities enacted only by males in Jian and Taiji’s performances re-establish the links between these gender practices and males in Chinese and Korean Society respectively, while denying females from enacting them in a public way. In so doing, the fraternity of Taiji’s performances resembles South Korean hegemonic practices that hold women back from active participation in public society, for example those which reduce the legitimacy of women’s work, denying them the status of labourers and associated social status and labour rights, among others (Kim, 2001; Song J., 2003).

SAMULNORI AND MASCULINITY

The inclusion of the band Samulnori into the “Hayôga” song and in the 93 Naeil ûn nûjûri live show, adds to the fraternity of “Hayôga” performances. One reason for this is that the band includes only male percussionists and t’aep’yôngso players. Samulnori is also a genre which has been marked masculine since its inception, and seems especially so when contrasted with other types of traditional Korean music visible in contemporary South Korea. As part of Korean ‘traditional culture’, Korean traditional and new traditional music (kugak and shin kugak) for different audiences and in multiple contexts has been assigned to “femininity” and often to females themselves in contemporary South Korea. Among this feminization of traditional musics such as P’ansori singing or music for kayagûm—evident in the very popular film released the same year as “Hayôga”, Sopyonje (Sôp’yônje, 1993, dir. Im Kwon-taek) —Samulnori and especially their rough looking and charismatic leader Kim Duk Soo (Kim Dôk-su), exert a tough, athletic or rugged masculinity (Park, 2000:87-88). This heroic masculine character is emphasized by Kim taking on an image as a hero or ‘great man’ of music and is made visible through their fame and popularity (much higher than for other traditional performers). In addition, this character has spread throughout the samulnori genre, as Samulnori has spawned hundreds of ensembles, predominantly formed of young males often copying Kim’s musical style and image (Park, 2000).

This heroic, rugged masculinity is not a marginal part of “Hayôga” as Samulnori, as band, genre, and sound, factor prominently into all three performances. Samulnori’s t’aep’yôngso solos in the music video account for 33 seconds of the music and are focal to the sound of the music video—mixed to the front, the piercing timbre of the t’aep’yôngso, it’s ‘foreign’ scale and tuning and the novelty of the instrument showing up in a popular song all factor together to make the solos stand out. The t’aep’yôngso solos are also highlighted in the video as points where The Boys show off their dancing skills, actions that are central to the video’s narrative energy. In the 1994 live performance, which is short at just under three minutes, one recorded t’aep’yôngso solo is included at the end of the performance of the song. The solo is mixed to the front and only supported by drum kit, over which Taiji and The Boys rap, which draws our attention to it. In the live 1993 TV performance (93 Naeil ûn nûjûri), Samulnori play a more important role, appearing live on stage with Taiji and Boys for most of the song. They come to the front of the stage to dance, spinning their sang-mos (ribboned hats) and drumming in a circle while Taiji and Boys move freely to the beat between the Samulnori members in a spontaneous un-choreographed manner. This occurs mid way through the performance for 22 seconds and at the end for 45 seconds. The overall effect of the movement of bodies, sounds of Samulnori’s drumming mixed with the electronic pop sounds, is of friends celebrating together. Because of the lack of females plus Samulnori’s rugged or athletic masculine image, a fraternity seems to be celebrating. Considering Baranovitch’s comments, the fraternizing displayed in this performance and the music video is less a simple presentation of the shinsedae spirit, and more a celebration of young men’s masculinity.

Admittedly, such a claim could be too simplistic or even unfair considering the important role female fans played in the Seo Taiji and Boys phenomenon. The incessant female screaming and singing-along evident in the 1993 performance and even more so in the 1994 concert where audience rapping and singing―trading lines with Taiji and the Boys―accounts for over one third of the performance, does form a major part of each performance and their success. However, just like the scores of young female fans who found satisfaction and some freedom through their adoration of Korean soccer players and were vital to the Red Devils phenomenon during the 2002 World Cup (Kim H. M., 2004), the female presence in the Seo Taiji and Boys phenomenon was relegated to off-screen, off-stage (off-field) supporting roles. This female presence, in both the World Cup and Taiji phenomenon, does little to lessen the emphasis on male camaraderie and displays of ‘male-only’ masculinities on stage, screen and field.

UP AGAINST PARENT CULTURE (AN ALTERNATIVE FRATERNITY)

Although the fraternizing in “Hayôga” performances certainly contributes to the hegemony of men (Hearn 2004) by excluding females from public participation, it is not necessarily hegemonic when placed in the context of other ways of being a man in contemporary South Korea. In his book The Remasculinization of Korean cinema (2004), Kim Kyung Hyun traces fraternities in Korean films through the 1980s to early 2000s and reveals they were formed in times of rapid change, trauma or uncertainty and in reaction against more powerful masculinist segments of society. Kim writes:

The “dominant fiction,” as described by Kaja Silverman, seeks to neutralize the shock of trauma by channelling the individual experience of disruption and disorientation into a collectivized sense of fraternal identity. … Likewise, in the Korean cinema the community symbolically functions to supplant the vanishing family and disavows the male protagonists' "lack" as they reestablish their social identities as workers, friends, or cells in gangster organizations. The external danger, in the midst of rapid changes, is at least temporarily subdued (2004:33).

Kim reveals this theme of fraternities and male “lack” in films from 1980 (A Fine Windy Day) through to 2000 (JSA, Kongdong kyôngbi kuyôk JSA, dir. Pak Ch’an-uk). As the characters in these films bond together in reaction against terrible conditions—those brought about by Park Chung Hee’s hurried modernizing campaign and resulting landlessness and escalation of migrant workers (A Fine Windy Day) or the prohibition of contact between North and South Korean soldiers in the Demilitarized Zone and the national security law (JSA)—so too do the characters in the “Hayôga” video, and in a more subtle fashion Taiji and Boys and their performance persona in the live performances. Here I have borrowed the idea of performance persona and character from Auslander’s (2004) clarification of ideas in Simon Frith’s book Performing Rites (1996), where popular music performances is understood to create meanings through three layers of performance. The three layers are: “…the real person (the performer as human being), the performance persona (which corresponds to Frith’s star personality or image) and the character (Firth’s song personality).” In “Hayôga” performances, all these layers work together to create meanings.

In the video, one threat that Taiji and Boys’ characters as well as their performance personas are up against is older generations’ conservatism and repression of teenagers. (Another is the threat of foreign masculinity and coolness, which I will discuss later on in this chapter). This theme is very explicit in the lyrics to Seo Taiji and Boys’ song “Classroom Idea” (“Kyoshil Idea”) from 1994, but holds much of the overall sensibility of the style, in sound, dancing, fashion and lyrics of the Taiji and Boys phenomenon. In the early 1990s, heightened consumerism and rapid growth of the culture industries led to fundamentally new realities and opportunities for youth in South Korea (Lee K-h., 2002: 47, Lee S-h., 2002; Kim, 1999). In his dissertation Toward a cultural history in the Korean present: Locating the cultural politics of the everyday (2002), Lee Kee-hyeung points out how most South Korean writing on culture in the 1990s emphasized the differences between the shinsedae and parent generations, especially in terms of consumerism (for example Jeon, 1998). Lee writes:

The New Generation that appeared in the 1990s displayed significantly different sets of socio-cultural conducts and interpersonal repertoire. Above all, the new generation was characterized by their radically new, "outrageous," "free-wheeling and "deviant"—from the viewpoint of dominant parent culture—social conducts and attitudes (2002:48).

Lee continues, "[i]n exemplifying the fault lines between the parent culture and New Generation Culture, no example was more telling then emerging local hip-hop culture and the cultural phenomenon called "Seo Taiji and the Boys” (2002:48). Although this generational divide can be overstated, as Lee acknowledges (2002:56), and differences in social values in the mid 1990s were more highly correlated to education levels than to age (Lee A. R., 2003), Taiji and Boys’ youthful rebellion, however vague in nature, was paramount in their performance persona and appeal. In “Hayôga” performances, visual and sonic parameters suggest youthful rebellion. Rebelliousness is particularly evident in the t’aep’yôngso solos sections of the “Hayôga” music video, suggested by new and ‘noisy’ parameters.

The new and/or noisy elements during the t’aep’yôngso solos of the music video include the hip-hop style dancing, quick use of camera zooms and handheld technique, lighting, and the t’aep’yôngso’s sound combined with fast moving, noisy rapping and bass line. The t’aep’yôngso sections in the video focus on dancing, drawing the viewer to The Boys’ hip-hop influenced dancing skills, a type and skill-level of dancing that was new in South Korea at that time. In addition, the second t’aep’yôngso solo section includes one Boy break-dancing, doing highly skilled moves on the floor. This type of ‘street style’ hip-hop dancing was remarkable, new even in underground scenes in 1993 South Korea. The newness of this dancing was evident in Yun-hûi’s exclamation recalling seeing Taiji and Boys on TV for the first time: “Wow!! What’s that!!”

The camera and lighting techniques used to shoot the dancing adds to the noisiness and the newness of these t’aep’yôngso sections. Fast in and out zooming is used at 2:38-39 when The Boys are dancing in unison in front of a bright white backdrop that creates an unstable, or noisy visual effect (see figure 12).

Handheld camera usage produces a similar effect when Taiji and the Boys are jumping and dancing together at 4:34. Especially effective use of handheld camera occurs at 2:34, 2:40, 2:47, 4:30, 4:33 and 4:43, when the camera shoots The Boys dancing using large movements but zooms in close and frames them very tightly. As a result, their movements are too large to fit the frame, and the shapes their bodies make slip quickly in and out of the frame. This effect, combined with the very bright backlighting and handheld camera, creates a very unstable, noisy visual display. This type of visual effect as well as the handheld camera technique on its own was also

rare in Korean music videos, unconventional for Korean television of the time, and contributed to the excitement of many young viewers.

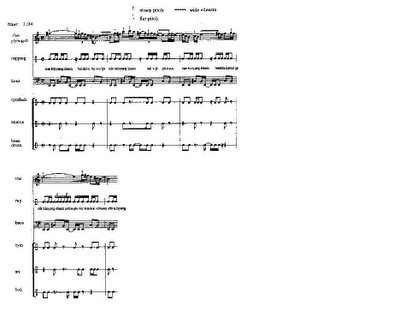

Combined with these disorienting ‘noisy’ camera and lighting techniques is the noisiness of the t’aep’yôngso’s piercing timbre,’ foreign’ scale, tuning and rhythm playing over equally noisy music. Despite the t’aep’yôngso being an old ‘traditional’ instrument, the novelty of using it in a popular song adds newness and excitement to the song. The t’aep’yôngso’s tonality is highly dissonant with the bass guitar and the tonality of the rest of the song as a whole. As indicated in figure 13, approximately half of the notes the t’aep’yôngso plays are noticeably higher or lower than those of the western scale to which the other instruments in the song are tuned.

This dissonance is especially noticeable on many held tones―the held E (raised E) notes in bars 2, 3 and 4 clash with the E notes played in the bass guitar. Although the piercing timbre and tonality of the t’aep’yôngso are what is most noticeably jarring, the rhythm of its lines also does not correspond to that of the drum kit, bass and rapping. The t’aep’yôngso’s rhythm does not conform to the 4/4 metre, for example the fast moving notes in bars 1 and 2 or the notes F - F - E - C - B from bar 2 to 3 which drag behind the beat. In addition, the t’aep’yôngso holds notes over most of the bar lines, its phrases not corresponding to these divisions. Under the solos, the bass line moves quickly and Taiji and Boys nearly shout their raps in rhythmically dense lines—many words crammed into each bar of music—which adds to the noisiness. Taiji and the Boys’ nearly shouted rapping is strongest on the words nan kûn’yang idaero in bars 1 and 3, and the rhythmically dense rap is most so in bar 4 (see figure 13). Taken as a whole, the t’aep’yôngso sections are new and noisy, which inform the overall sensibility of the “Hayôga” music video.

This dissonance is especially noticeable on many held tones―the held E (raised E) notes in bars 2, 3 and 4 clash with the E notes played in the bass guitar. Although the piercing timbre and tonality of the t’aep’yôngso are what is most noticeably jarring, the rhythm of its lines also does not correspond to that of the drum kit, bass and rapping. The t’aep’yôngso’s rhythm does not conform to the 4/4 metre, for example the fast moving notes in bars 1 and 2 or the notes F - F - E - C - B from bar 2 to 3 which drag behind the beat. In addition, the t’aep’yôngso holds notes over most of the bar lines, its phrases not corresponding to these divisions. Under the solos, the bass line moves quickly and Taiji and Boys nearly shout their raps in rhythmically dense lines—many words crammed into each bar of music—which adds to the noisiness. Taiji and the Boys’ nearly shouted rapping is strongest on the words nan kûn’yang idaero in bars 1 and 3, and the rhythmically dense rap is most so in bar 4 (see figure 13). Taken as a whole, the t’aep’yôngso sections are new and noisy, which inform the overall sensibility of the “Hayôga” music video. In his article "Louder than a Bomb": The cultural politics of hardcore rap in the U.S. and Korea” (2001) Roe suggests that the sound and attitude of South Korean rap music is at the core of its rebelliousness, specifically directed against adults:

Ultimately, [Korean] hardcore rap speaks for one of the most voiceless groups in Korea, namely teenagers; for Korean teenagers, who often feel like they are suffocating under the weight of school, family and traditional values, the sound and attitude of hardcore rap signify as much as its overt political messages (117).

Similarly emphasizing the importance of the sound of rap music in his study of the American rap group Public Enemy’s song “Fight the Power”, Robert Walser (1995) argues that the explicit and intentional noisiness of this song pushes it beyond ‘normal’ musical boundaries and in so doing is a type of rebellion—a rebellion of youths versus adults and not simply of black Americans versus white Americans. So too does “Hayôga’s” noisiness go beyond ‘normal’ musical boundaries (especially the mix of a traditional Korean instrument into a rap song) like the ‘noisy’ visual elements of the video push the boundaries of South Korean television conventions. For this reason—the youth versus adult rebelliousness created by the sounds and images of the video—I am uncomfortable labelling the fraternity exhibited in this performance, as well as in the live performances, as hegemonic. My reluctance is important to understand the significance of Taiji and Boys rebelliousness in terms of gender.

Although excluding females from participating in this rebelliousness onstage and on screen, the fraternity in “Hayôga” is ‘acting-out’, like Hyôn-su in the movie Once Upon a Time in High School, against more powerful segments of society, namely parents and the school system. Significantly, “Hayôga” performances are rebelling against an adult society that is heavily gendered. The adult society that Taiji and Boys are acting out against is, at its core, reliant on the subjugation of women and on powerful forms of masculinity as men’s—militarized for instance as indicated by Moon (2005). Then, like Once Upon a Time in High School, these pop-culture performances simultaneously celebrate and confirm the masculinity of young males while chipping away at a strongly masculinist and suppressive adult society, leaving them ambiguously placed within South Korea’s gender hierarchy.

Despite being unwilling to conclude that the fraternity enacted in “Hayôga” performances participates in the construction of hegemonic masculinities, I am troubled by the invisibility of this fraternity to fans and writers alike. Fraternity standing in for youth reveals the taken-for-granted power processes (Hearn, 2004) that males have even in youth cultures such as the Seo Taiji and Boys phenomenon. That the absence of females, except as fans, in Taiji and Boys’ performances is not acknowledged either by scholars who have written about the phenomenon or by most fans, illustrates the pervasiveness of males’ taken-for-granted power in South Korea.

[1] It should be noted that it is difficult to agree that the dismissal and marginalization of women in popular music is common everywhere as Willoughby suggests. For example in recent decades, female popular music performers in Canada have been much more successful in terms of international fame and selling power than their male counterparts (Celine Dion, Alanis Morissette and Avril Lavigne are examples).

[2] See Abelmann (2003) and Choi (2002) on traditional culture and arts in contemporary South Korea and the contradictions and complexities of the gendered sign systems shaping how they are perceived.

[3] See Choi (2002) on gender and traditional music in Sopyonje.

[4] The concept of heroes or ‘great men’ of music had not significantly factored into Korean traditional music prior to the 1970s (Killick 1991; Howard 1998). Kim Duk Soo is the performer who has most often been promoted as a ‘great man’ of Korean music. For example, he even had an album and concert titled Mr. Changgo to commemorate his 30 years as a performer. For more on the reception and promotion of Kim Duk Soo as a hero or ‘great man’ of Korean music see Park 2000: 9-10).

[5] For more discussion of the role of Seo Taiji fans in cultural production, see Pak (2003) Lee K-h. (2002) and Young (1999).