Seo Taiji 1992-2004: South Korean popular music and masculinity (my master's thesis)

© Janet Hilts 2006 - please note: this is not the final version of my thesis.

In this first section, my analysis focused on fans’ responses to my questions concerning the relationship, or lack of relationship, between the sound of popular music and gender. I also paid attention to their talk at other points in our discussions as well as their overall attitude and style of communication during the whole interview process. Upon doing this, I noticed that most fans’ conceptions of music and masculinities and femininities ranged from ideas that music is quite flexible in how it can express gender, including a variety of genders, to that where music really only can express extremes or stereotypes of masculinity or femininity. I was surprised that only one fan, Chang-to (24), believed that music does not express gender, or that music and gender are unrelated things.[1] Some fans spoke more confidently than others about these issues, and most fans’ communications indicated a mixture of conventional thinking about gender as a binary system (men versus women, masculine versus feminine) and a more contemporary type of thinking where masculinity and femininity are more fluid and unstable. I will begin with those who tended more towards this newer way of thinking, and end with those who tended toward the more conventional way.

I asked fans to discuss their ideas and feelings about music and gender, a difficult topic to be sure, because I respected that they could deal with challenging topics. For the most part fans stepped up to this occasion and a number gave explanations and elucidations that would match those from many a popular music graduate seminar, for instance.

To present fans’ tendency to think about masculinity and femininity as quite fluid and changeable, and where music is successful in expressing this, I will focus on the talk of Yong-t’ae. Other fans who expressed similar conceptions of gender and music were Kang-t’ae and Yun-hûi. Some of Yong-t’ae’s opinions are shown in excerpt 1, where we can also see an example of a rather confident expression of the relationship between music and gender.

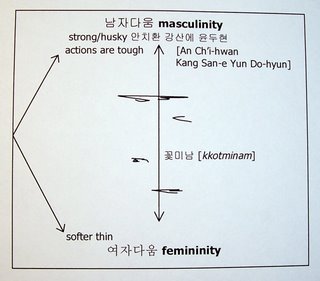

Yong-t’ae (32) began his explanation with little hesitation and very systematically. True to his organized, logical, and keen approach to all of our interviews together, he structured his talk around a diagram of gender, which he drew out on a piece of paper. At first glance, it is perhaps not obvious that Yong-t’ae’s talk is particularly contemporary, sensitive to the complexity of gender and of gender change. Yong-t’ae began his talk with a dichotomy (actually marking one on paper, see figure 1), a description of masculine versus feminine vocal style and movement or appearance.

He described with assurance the idea of strong husky voices as masculine and thin soft voices as feminine for instance and easily fit rockers and the folk song singer whom he likes into the masculinity box. However, quickly as his talk went on, he spoke about how other female and male singers would fit into various positions between the points masculinity and femininity took on his paper. To illustrate his point visually, he often (at this point in our conversation and again towards its end) pointed to various places between the words masculinity and femininity on his sheet, sometimes scribbling a mark, when talking about genders other than gender extremes.

He described with assurance the idea of strong husky voices as masculine and thin soft voices as feminine for instance and easily fit rockers and the folk song singer whom he likes into the masculinity box. However, quickly as his talk went on, he spoke about how other female and male singers would fit into various positions between the points masculinity and femininity took on his paper. To illustrate his point visually, he often (at this point in our conversation and again towards its end) pointed to various places between the words masculinity and femininity on his sheet, sometimes scribbling a mark, when talking about genders other than gender extremes. In short, he expressed that gender in the vocal style and appearance of singers is on a scale, and not necessarily linked specifically to male or female bodies. He expressed that there is a grey area, a mixed gender area in between―chungsông, he chose the English word unisex―which is important to the appeal of newer South Korean singers today. Yong-t’ae feels a singer’s music and image belong somewhere on his chart and each spot on his chart (each gender) is meaningful, not simply expressing a singer’s personal characteristics.

Yong-t’ae also indicated his sense-making of gender in South Korea is quite contemporary, or transitional, and he talked ambivalently about ‘conservative’ versus ‘progressive’ behaviours and attitudes. He gave a somewhat open-ended reaction to the younger male singers who belong close to the word “feminine” on his paper: he dislikes them for seeming un-Korean and too female in appearance, but respects his nephew’s decision to like them. His comment “I’m Korean. Very conservative Korean” for why he does not personally like these ‘feminine’ singers could lead us to believe that he ascribes to ‘conservative’ values, concerning gender for instance. To some degree, this could be true, but aspects of his talk elsewhere, and his laughter following this remark, indicate he is aware of the grey area a ‘conservative’ versus ‘progressive’ binary erases. In talking about his father, for instance, Yong-t’ae described him as conservative but also went to lengths to explain how his father, a farmer now in his seventies, did not entirely have the ‘normal’ masculinity of his generation. He explained how his father behaves at certain times in atypical ways within his family: for example working as hard as his wife to prepare for ancestral worship ceremonial holidays and expecting his sons to do the same. In addition, he expressed dissatisfaction about younger Koreans studying in Canada and spoke about how they believed they were progressive but in fact how they were very conservative. Specifically he expressed dissatisfaction with their ‘conservative’ attitudes concerning gender norms, in comparison to Canadian women whom he was simultaneously surprised by and admired: women who “just enjoy playing sports or, they just do, they just want to do something they just try try, they don’t care about their age or, maybe, other people’s opinions, they, want to be someone or they want to do, I think they just try.”

Given this context then, it remains ambiguous whether Yong-t’ae prefers the rockers Yun Do-hyun and Kang San-e and the folk song singer An Ch’i-hwan because their voices and images are conventionally masculine to him. Although he dislikes male singers who are too stereotypically feminine in their vocal style and appearance, he also expressed reservations toward what he referred to as conservative or traditional (once he described theses as Korean) formations of gender.

Excerpt #1

Yj: I want to divide, masculinity and femininity (writes each word down on his sheet of paper. “Masculinity” toward the top of the page and “femininity” toward the bottom). Especially singers. [Right, sure]. Ah. (Points to masculinity) The voice is very, strong, or very husky? And ah, their actions are more, more tough than, women singers. [Ok] And ah… but women singers, are softer, softer than, in appearance and sound, ya the voice is a little bit thin, not strong. But you know, some Korean women singers has, have a very, strong strong voice. Yes and so, in these cases (pointing near the word masculinity). I said to you, (pointing at word masculinity) Kang San-e, Yun Do-hyun, [uhuh they’d fit there] uhuh and another singer, An Chi-hwan (writing it down), ok, he is also very famous. These singers’ voices, are very strong. They are, maybe, these guys are rockers (points to Yun Do-hyun and Kang San-e written on his paper) but he (points to An Chi-hwan) is a folk song singer. Yes a folk song singer, but his voice is very unique, very special [ok]. He also…worked for a social organization. [Oh ok] when Korea, had ah, anyways he had a time (dealing) with politics. Yes but I dunno femininity but, these days, most ah, most Korean singers, for teenagers, singers including men and female singers their voice is a little bit, softer than, the time before. [Ok] Their, I found this word [We look up the word chungsŏng--neutral gender or androgynous, literally “gender in the middle.” We discuss vocabulary together and look in our dictionaries]. Masculinity plus femininity (points to spaces between the words masculinity and femininity).

J: A better word would be […] androgynous.

Yj: Yes or unisex? Their hair is very long. Very long and ah, sometimes they had cosmetic surgery? [Yes] Yes they are very tall, but actually they are not typical Korean appearance [right uhuh]. A little bit… I don’t like them. I’m Korean. Very conservative Korean (smiles). But my, my nephew, likes their songs, and so of course I respect his choice. Ah. Yes I agree with this one (points to question #6 concerning a relationship between music sound and gender).

In Yong-t’ae’s comments, as in those of Kang-t’ae, Chae-tol and Yun-hûi’s, there is acknowledgement of various forms of masculinity and that certain singers match certain types. However, it remains unclear what his judgments of masculinities are and how his perceptions of masculinity in music affects his choices in favourite singers. From the ways in which Yong-t’ae debated ideas in a dynamic way during our conversations (even when we were basically chatting about ‘simple’ aspects of popular music), his talk about masculinity and popular music indicate his ideas are very much under construction and the process with which he makes sense of gender is ongoing. As such, like Kang-t’ae and Yun-hûi especially, Yong-t’ae’s talk participates in the flux and transformation of gender in contemporary South Korea.

[1] To help non-Korean speakers keep track of the fans in my study, the pseudonyms I chose are organized in the following way: For males, the second half of their name begins with the letter t (or t’). For females, it begins with the letter h. Fans in their 30s have a name beginning with Y; the names of fans in their upper twenties begin with K; the names of fans younger than 26 begin with Ch.

Previous posts

- [ch. 2] Popular music and gendered meanings cont.

- [ch. 2] Taiji and gender 1

- [ch. 2] Taiji and gender 2 & Conclusion

- Vignette # 2

- CHAPTER 3: Alternative masculinity through Seo Tai...

- [ch. 3] Vocal sound and gender

- [ch. 3] Seo Taiji & Boys’ soft, slow songs

- [ch. 3] Taiji’s vocals in relation to hegemonic ma...

- CHAPTER 4: The relationship of “Hayôga” performanc...

- [ch. 4] Fraternity