Seo Taiji 1992-2004: South Korean popular music and masculinity (my master's thesis)

© Janet Hilts 2006 - please note: this is not the final version of my thesis.

Yun-hûi: (We are listening to “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”. She seems to be listening carefully and looks very serious. She speaks confidently) Yes I feel Seo Taiji in this song is not like a man, but like a teenager, or boy [uhuh]. Boys, boy, who is not decided by a gender standard. So not a man. So that’s a, that’s a strong point of Seo Taiji [uhuh]. He looks, looks like a boy, not a man [uhuh].

Yong-t’ae: (We are listening to “Nôege”, from the 3rd album. He has chosen to listen to this song first out of his selection of songs to listen to together. We are sitting in the park and he listens calmly. He answers my question to why he chose this song): Melody. I like this melody…Voice is very different from Kang San-e and Yoon Do-hyun, strong. (Taiji) sounds like a woman, (sounds) soft and weak. (He smiles, sitting quietly and listening without saying anything). This was a big hit (smiling and thinking). My friends and I, we enjoyed this song (smiling).

For Yun-hûi and Yong-t’ae, Taiji’s ballad songs, in these cases “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro” and “Nôege” illustrate how Taiji is different, different in terms of gender, specifically not ‘like a man’. In Taiji’s singing and lyrics in “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, Yun-hûi can feel the childlikeness of Taiji, the absence of masculinity, a characteristic that she is especially fond of in Taiji. “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, Yun-hûi confidently indicates, illustrates this characteristic especially well. Similarly, Yong-t’ae talks about “Nôege” and clearly indicates that Taiji’s voice starkly contrast that of the rockers Kang San-e and Yun Do-hyun, precisely because Taiji sounds like a woman. Yong-t’ae and his friends had enjoyed this song considerably, enough for Yong-t’ae to choose to listen to it with me and to listen to it first, not necessarily because of Taiji’s singing, but certainly for its gentle melody that Taiji carries with his soft, weak voice. In this chapter, I want to investigate in some detail Taiji’s singing in these songs, to help us to understand what makes Taiji seem not ‘like a man’ in his ballads for fans such as Yun-hûi, Yong-t’ae among others. Specifically, I want to illustrate how Taiji’s soft vocals in his early slow songs are ‘different’, in other words, how they differ from hegemonic masculinity in contemporary South Korean society. The central important characteristics of his vocals of central importance here, is timbre, what Yong-t’ae focused in on and referred to as Taiji’s soft, weak ‘feminine’ voice, as well as aspects of the timbre’s envelope (ornamentation and inflection, vocal attack, range). I will follow a presentation of the gentle and “cute” (yeppûn or kwiôun) elements of Taiji’s vocal style in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô”, “Nôege” and “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro” with a discussion of their contestation of hegemonic masculinity. These songs’ lyrics translated into English are shown in Appendix B. Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro

I summarize the vocal parameters used in the three songs in Appendix C. In “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and “Nôege” a number of different voices and vocal deliveries are used, including rapping. The vocal deliveries/types and when they occur in these songs are listed in figures 2 and 3. In “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, fewer different vocal types are used (see figure 4). Taiji’s sung vocals in each song, the vocal types labelled V1 (as well as V2 in “Nôege”), are relatively high, very soft with an open light timbre, attack notes lightly, use very little or no ornamentation or vibrato, and use a small vocal projection that is miked closely. A number of strategies are used to highlight the soft vocal timbre Taiji uses in his ballads involving changes in texture, vocal articulation and inflection and contrasts with other vocal strategies. Taiji’s voice in these songs is used to evoke extreme gentleness or tenderness, cuteness as well as sincere emotion, characteristics that one fan on Taijimania.com’s community forum is longing to hear more of:

Taiji’s sensitive emotional (kyanalp’û), tender (yôrin) voice…[…] All of a sudden Taiji’s voice from his earlier days… listening to “Yôngwôn”… “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, I’m really really missing the voice used in these songs. […] Taiji’s voice when he sings ballads is so sweet (kammi) it melts my heart […] Anyways… so Taiji’s voice is beautiful and cute (ch’am kopko and yeppû]? (Purûlsaekttongkko, 2003. – a female fan).

Other fans use a similar vocabulary to describe Taiji’s voice in his ballads, which they defend and celebrate. Here are two more examples:

I couldn’t hear so well but the one thing I remember [from Taiji’s concert on the 25th and 26th of October, 2002] is that his voice was so sweet/beautiful [koun]. Today he was sitting on a chair, singing [the ballad “Nôlchiuryôhae”], his voice was really sweet/beautiful. His gentle [pudûrôun] voice in “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro” on T’aeji-ûi Hwa isn’t comparable because the voice in “Nôlchiuryôhae” is so freaking good. Totally singing sorrowfully and so cutely [aejôrhage and yeppû) (Take3, 2002. – a male fan).

Taiji’s voice is really cute (yeppû]. Hee hee. I think, “If you wanna succeed in becoming a rock star, your voice should be big and rough” it seems this is [now] actually a stereotype in Taiji’s thinking. Even though big and rough voices are good, a delicate (sômsehan] voice like Taiji’s is also good (Take..+two, 2003).

In the remainder of this section, I will try to highlight the musical characteristics that bring these fans to carefully attend to and fully enjoy Taiji’s ballad singing.

In "Aidul-ui nun-uro”, which does not include any rapping, Taiji's soft singing style is the central vocal delivery of the song. Taiji's light and thin vocal timbre is emphasized at the end of a few sections by having the instrumentation (texture) and volume drop back suddenly to foreground Taiji's light vocals by contrasting them with the fuller instrumentation. This happens at 4:03 when the drum kit, bass synthesizer, backing vocals and moving string lines drop away to highlight Taiji's voice on the syllables shi’pûnde, supported only by sustained strings and piano chords and then a gently moving piano and flute line. The same effect occurs at 4:48 at the end of the song where the drum kit, bass synthesizer, strings, children’s chorus and piano’s broken chords drop away leaving Taiji’s soft voice on the words saranghae chuseyo supported only by sparse piano movement. This reduction in texture and volume effect also happens to a lesser degree at 3:09.

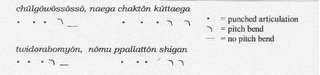

To sound sweeter in “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, Taiji sings some strings of words in the chorus with a slightly detached or punched articulation bringing a light bounciness to the chorus. This cute sound is also emphasized by pitch bends, dropping down to the pitches of the words following the lightly punched words. This happens at 1:47 and 3:33 on the words chûlgôwôssôssô naega chaktôn kûttaega and at 2:02 and 3:49 on the words twidorabomyôn nômu ppallattôn shigan:

In many ways Taiji’s clear timbre, lack of vibrato and cute effects such as these above, draw parallels with children’s voices, matching with the children’s chorus and lyrics of this song.

Taiji’s clear soft sung vocals in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and “Nôege” create a similar effect as in “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”. Similar to the lightly punched words in “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, in the verses of “Nôege” Taiji sings the words naûi maûmsogen kûnsimi saeng’gyôtchi (2:24) and then nôl saeng’gakhamyôn kat’ûn hansumppunman (2:33) in a light bouncy manner. To some fans, these vocals also sound childlike: “It’s been a long time since I listened to “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô”, once again his voice sounds childlike (aettoen)” (Namurang, 2002).

To some degree Taiji’s delicate voice in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” is highlighted by its subtle contrast with other vocal strategies used in the song. Taiji’s soft sung vocals (V1) contrasts with the brighter more intense timbre of V3 (Taiji and Boys harsher, more forcefully delivered singing) paired with the gritty timbre of the alto saxophone improvising alongside V3’s melody evident in the extended ending of the song. This transition in timbre can be heard from 3:21 – 3:37. The clear timbre and soft delivery of V1 is also contrasted with the bright timbre and more intense falsetto voice it trades lines with at 1:29-1:50 and again at 2:56-3:28.

Although Taiji’s soft sung vocals do much to evoke a gentle and cute sensibility—kammi, aettoen, yeppûn and yôrin—and combined with their lyrics and the conventions Korean ballad (palladû) songs, sincere emotions, his rapping style used in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and “Nôege” highlight similar characteristics to a greater degree, in fact to an extreme degree. Taiji’s rapping here is quite distinctive; prompting Kang-t’ae to remark it sounds strange— “kind of crazy”—and “definitely yôja kat’ae.” To me, Taiji’s rapping style in these songs is what is most distinguishing and fascinating about these songs, not only simply in terms of being uncommon but in terms of masculinities which I will discuss following further description. In combination with a similar timbre to that used in his soft sung vocals, Taiji uses pitch, a specific combination of accents with timbre, consonant pronunciation and choice as well as inflections in his rapping style. These characteristics contribute to the mild, tender sensibility (perhaps also vulnerability or passivity) and an especially childlike or girlish sweetness of the songs to which fans are responsive. Taiji’s rapping vocal timbre in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and “Nôege”, forming the focal points, or rapped choruses of these songs, is just as clear and soft as in his soft sung vocals and has more breathiness. This timbre, as well as a very light vocal attack, is highly noticeable in these songs not only because it is so uncommon among Korean rappers but also because it is used in the focal points of these songs and Taiji’s voice is mixed to the foreground, especially evident in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô.”

In combination with this light, thin timbre, Taiji raps at a relatively high pitch centering around the pitch a in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and around c1 in “Nôege.” These pitches are noticeably higher than his natural speaking voice, which can be heard at the beginning

of “Nôege,” and adds to the sweetness and aettoen (childlike) or yôja kat’ae cuteness of the song

[2]

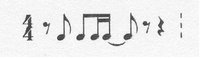

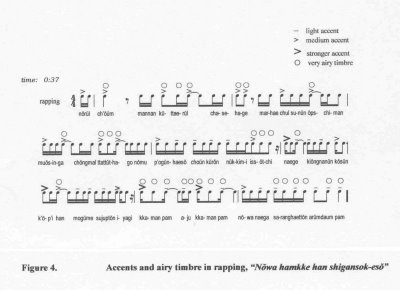

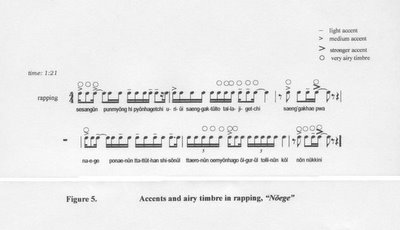

Taiji highlights this light, thin timbre by combining it with accented syllables. Figures 4 and 5 show the accents and usage of an especially airy timbre in sections of “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and “Nôege” respectively. In “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” this combination is most noticeable in the first rapping verse on the lines nôrûl ch’ôûm manan kûttae-rûl chasehage marhae chul sunûn ôpschiman (0:37-0:43) and kkaman pam aju kkaman pam (0:56-0:59) among other moments. The second verse does not use so much of this combination, combining most accented words with a more moderately soft thin timbre. However, a very thin timbre can be heard on some stressed words, for example alge twaessô (2:16), oraen (2:17), hûrû-nûn norae (2:24). In “Nôege”, the combination of a soft airy timbre and accented syllables is most noticeable when Taiji repeats words sung by the Boys. This happens with this rhythm:

on the words saeng’gakhae pwa (1:27 and 3:13), nôn nûkkini (1:40), alsu inni (3:23) as well as near the end of the song on the words nôn ajikto (3:51).

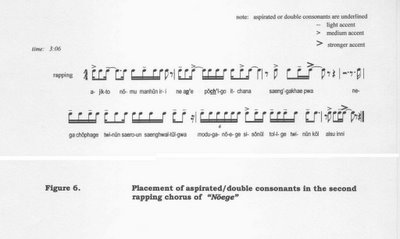

Taiji also emphasizes gentleness in his rapping style in these two songs through his choice and pronunciation of consonants. Much Korean rapping makes noticeable use of the aspirated and double consonant sounds in Korean as well as the tendency for younger Koreans to over- enunciate softer consonants such as chiût, kiyôk and miûm. This over-enunciation, evident in the rapping by the rappers in DJ Doc and Deux (Dusû), and by Cho PD among others, helps to give Korean-language rap a kinetic and sometimes an aggressive quality. In contrast, Taiji in these two songs underemphasizes these harsh consonant sounds. This under-emphasis is noticeable throughout all of his rapping in “Nôege” and in the second rapping verse of “Nôwa hamge han shigansokesô.” In these sections, Taiji underemphasizes these consonants by using few of them and by not placing many of them on accented syllables. For example in the first rapping chorus of “Nôege” Taiji includes only four aspirated or double consonants (out of a total of sixty six sounded consonants), three heard in the line ttattûthan shisôn-ûl ttaeronûn oemyônhago (1:34) and one in nôn nûkkini (1:40). Within theses, only kki is placed on an accented syllable. In the second rapping chorus of “Nôege” Taiji includes only two aspirated or double consonants (out of a total of seventy one sounded consonants) heard in the line ne ap’e pôch’igo itchana (3:09). The p’iûp (p’) is placed on an accented syllable (see figure 6).

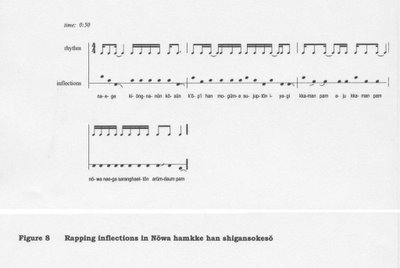

More important in evoking a sweet, cute sensibility (kami/koun, yeppû) than this light usage of consonants is Taiji’s pronounced inflections in his rapping in these two songs. In his rapping, Taiji’s pitches undulate, considerably more than in men’s styles of spoken Korean and more than is noticeable in Korean rapping generally. As a result, these undulations come across as keenly yôja kat’ae, and most certainly would not be acceptable to the middle aged men in the vignette preceding this chapter. Taiji further combines these undulating inflections with pitch bends, rising to pitches, small fall-offs and so on. See figures 8 and 9 which give an approximate visual representation of some of Taiji’s rapping inflections used in “Nôege” and “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” respectively. Particularly cute sounding undulating pitches can he heard in “Nôege” on the lines sesang-ûn punmyônghi pyônhagetchi (1:21), Nôege ponae-nûn ttattûthan shisôn-ûl (1:33), and saeroun saenghûiltûl-kwa (3:20). An especially noticeable example of these undulating pitches in “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” is on the line k’ôp’i han mogûme sujuptôn iyagi and continues with the repeated words kkaman pam (0:53). Similar sounding pitch bends can be heard in “Nôege” on the syllable pwa in saenggakhe pwa (1:27), the syllable ni in nôn nûkkini (1:40), the syllable e in nae ap’e (3:09), and the syllable kwa in saenghûiltûl-kwa (3:21). In “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” these cute bends are especially noticeable on the word pan in the lines kkaman pam aju kkaman pam (0:56) and arûmdaum pam (1:01). Taiji’s many pitch bends in these songs are striking in how they recall extremely girlish speaking styles of young Koreans, prompting Kang-t’ae to label them yôja kat’ae with certainty.

Taken together, Taiji’s soft, clear vocal timbre combined with the various vocal parameters and musical strategies I have outlined do much to emphasize an assortment of gentle and cute characteristics, sounding aettoen, yôja kat’ûn, yeppûn, yôrin, pudûrôun, sômsehan and so on. Indeed Taiji’s vocals in these songs are some of the most extreme examples of a male expression of cute and gentle characteristics in Korean popular music.

Combined with the conventions of slow pop or rock songs, known as ballads (palladû) in Korean popular music, a genre that emphasizes heartfelt emotions as well as lyrics that fall neatly into this tradition, Taiji’s songs also render gentle sincere emotions, as indicated in fans descriptors for his ballad singing: aejôrhage (sorrowfully) and kyanalp’û (sensitive, emotional). The words of a number of lines I have mentioned already as examples of cute or gentle sound, also illustrate the sincere emotions of the ballad genre. An example from“Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”, the line twidorabomyôn nômu ppallattôn shigan (2:02 and 3:49) mentioned for its cute bounciness and pitch bends, makes up part of an introspective line that translates as “When I remember the time of pure, clear hearts [childhood], I realize it has passed so quickly.” Similarly voicing emotional introspection and sung in a cute, light way are the lines in ”Nôege” naûi maûmsogen kûnsimi saeng’gyôtchi (2:24) and then nôl saeng’gakhamyôn kat’ûn hansumppunman (2:33) which translate respectively as “worries come into my heart” and “when I think of you I feel as if I am sighing deeply.” An example of sincere emotional lyrics from rapping are the words sung with girlish (yôja kat’ûn) inflections k’ôp’i han mogûme sujuptôn iyagi and kkaman pam achu kkaman pam which form part of the line that translates as “I remember taking a sip of coffee and a timid story. Dark night, very dark night. You and I loved, beautiful night,” in Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô”(0:53). Musical conventions borrowed from the ballad genre used in these three songs, instrumentation and rhythmic groove, also underscore their emotion and gentleness. Since the late 1980s up to today, piano and/or strings (sometimes synthesized) as accompanying instruments and a saxophone playing jazz-pop style solos and melodic accompaniment figure prominently in the Korean ballad genre and have become signs that help to signify the genre’s emotionality, tenderness and romanticism. Piano is an accompanying instrument in all three of the songs and is the primary accompanying instrument throughout all of “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro” and throughout most of “Nôege” at times combined with a lightly played electric guitar. Strings also figure prominently in ”Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro”. Sax solos and accompaniment are included in two songs, gritty jazz style alto sax lines in ”Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” and pop/smooth-jazz style soprano sax lines of “Nôege”.

The rhythmic groove of “Nôege” and “Aidûl-ûi nun-ûro” shares with most ballads a lack of rhythmic play between musicians, creating a very straight rhythmic base for the songs. These songs’ lack of rhythmic tension, which often creates a sense of dynamism and is suggestive of movement or dance, emphasizes the gentleness or even passivity of these songs. “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” deploys much more rhythmic tension, especially evident in the loud bass-line, situating it somewhere between the ballad genre and the reggae and hip hop influenced pop music being introduced to South Korea by Taiji, Kim Gun Mo (Kim Kôn-mo), Lee Seung Chul (Yi Sûng-ch’ôl) or Lee Hyun Woo (Yi Hyôn-u) in 1992. “Nôwa hamkke han shigansok-esô” then provides a more active and engaged rhythmic base to Taiji’s soft more mild vocals.

[1] The word “cute” does not register quite the same in Korean as it does in English. In English it can carry an element of disingenuousness but in Korean it just means sweet, pretty or attractive, lovable and childlike. In South Korea, like Japan, extremely cute things abound and are not just targeted at the young. For example, in South Korea the police have a mascot whose picture is used on signs and pamphlets which looks, to Westerners, like a character from a children’s cartoon and decidedly out of place. Being cute (kwiôp-ta) is also often gendered and can be a desirable characteristic in women and not just girls. This behaviour is also increasingly becoming a characteristic of many young men. Other words which can describe Taiji’s cute voice reflect the gendered element of sweet, childlike things popular in South Korea: yôja kat’ae (literally “like a girl”) or kijibae kat’ae (which means “like a girl” but in a derogatory manner).

[2] Pitches are denoted with the standard system: c2 is one octave higher

c1 is middle c

c is one octave lower

C is two octaves lower

[3] For an introduction to the conventions of the Korean ballad genre in English, see Howard 2002.

[4] See Keil (1994) for discussion of the importance of the relationship between rhythmic grooves and embodied feelings to understanding music.